|

|

|

#181 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

| The Following 3 Users Say Thank You to Mister Bent For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#182 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Ezee and I like to start out our day with a little calisthenics - keeps us looking young!

We get our cardio workout in the racism thread. It's not easy being retired!

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to Mister Bent For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#183 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Morning reps.

__________________

|

|

|

|

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to Queerasfck For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#184 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

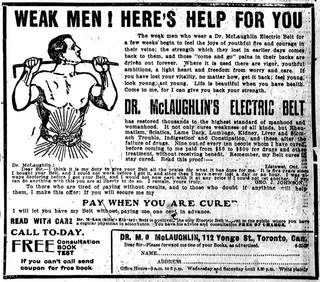

...but for those of you who aspire to the svelte physiques of the bromosexual set:

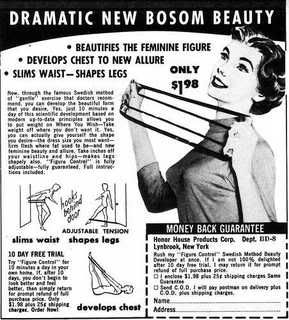

I haven't forgotten the ladies! For that dynamic torpedo-look bust:

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Mister Bent For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#185 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Quote:

__________________

|

|

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Queerasfck For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#186 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Wow! No wonder you're such a happy fella!

I'm on my way over, think she'll give me a preview?

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

|

|

#187 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Quote:

__________________

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

#188 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Quote:

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Mister Bent For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#189 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Although, Mister Bent does enjoy showing off his pipe.....

__________________

|

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Queerasfck For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#190 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Just don't try smoking it!

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Mister Bent For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#191 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

Satan in a Sunday Hat Preferred Pronoun?:

Maow Relationship Status:

Married Join Date: Jan 2010

Location: The Chemical Valley

Posts: 4,086

Thanks: 3,312

Thanked 8,740 Times in 2,566 Posts

Rep Power: 21474857            |

Dirty. Both of you.

__________________

bÍte noire \bet-NWAHR\, noun: One that is particularly disliked or that is to be avoided.

|

|

|

|

|

|

#192 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

We are not!

See? We have soap. Now be a dear and pick it up for me?

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

|

|

#193 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

Satan in a Sunday Hat Preferred Pronoun?:

Maow Relationship Status:

Married Join Date: Jan 2010

Location: The Chemical Valley

Posts: 4,086

Thanks: 3,312

Thanked 8,740 Times in 2,566 Posts

Rep Power: 21474857            |

I think instead I am gonna say NO, then GO, and TELL someone I trust.

__________________

bÍte noire \bet-NWAHR\, noun: One that is particularly disliked or that is to be avoided.

|

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to betenoire For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#194 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

. Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: .

Posts: 2,905

Thanks: 4,151

Thanked 5,824 Times in 1,722 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Quote:

I'm sorry? Is this like that newfangled Stop, Drop and Roll? Kids these days, I never can keep up!

__________________

Every normal man must be tempted at times to spit on his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats. - H. L. Mencken |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#195 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

Satan in a Sunday Hat Preferred Pronoun?:

Maow Relationship Status:

Married Join Date: Jan 2010

Location: The Chemical Valley

Posts: 4,086

Thanks: 3,312

Thanked 8,740 Times in 2,566 Posts

Rep Power: 21474857            |

Quote:

You know. What do you do if you're walking home from school and a stranger offers you a ride? NO-GO-TELL! You say NO, then GO, and TELL someone you trust! I'm surprised you don't remember this? Maybe they were only aired in Canada.

__________________

bÍte noire \bet-NWAHR\, noun: One that is particularly disliked or that is to be avoided.

|

|

|

|

|

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to betenoire For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#196 |

|

Member

How Do You Identify?:

A pretty little thing Preferred Pronoun?:

Fatale Relationship Status:

Independently owned and operated Join Date: Apr 2010

Location: Afternoons in Utopia.

Posts: 832

Thanks: 1,090

Thanked 1,292 Times in 486 Posts

Rep Power: 3051091            |

This place is nasty. A lady can't walk in here without concern that she is going to step in something repulsive.

Can you please hire a maid or something...?

|

|

|

|

|

|

#197 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Quote:

__________________

|

|

|

|

|

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to Queerasfck For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#198 |

|

Member

How Do You Identify?:

A pretty little thing Preferred Pronoun?:

Fatale Relationship Status:

Independently owned and operated Join Date: Apr 2010

Location: Afternoons in Utopia.

Posts: 832

Thanks: 1,090

Thanked 1,292 Times in 486 Posts

Rep Power: 3051091            |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#199 |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

still ballin' Relationship Status:

Triple X Join Date: Nov 2009

Location: west side

Posts: 2,544

Thanks: 5,716

Thanked 6,486 Times in 1,638 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Maid's day off. But feel free to clean if you want.

__________________

|

|

|

|

| The Following 2 Users Say Thank You to Queerasfck For This Useful Post: |

|

|

#200 | |

|

Senior Member

How Do You Identify?:

bigender (DID System) Preferred Pronoun?:

he/him or alter-specific Relationship Status:

Unavailable Join Date: Apr 2010

Location: Central TX

Posts: 3,538

Thanks: 11,051

Thanked 13,969 Times in 2,590 Posts

Rep Power: 21474855            |

Greyson recommended I post this here

Quote:

__________________

I'm a fountain of blood. In the shape of a girl. - Bjork What is to give light must endure burning. -Viktor Frankl

|

|

|

|

|

| The Following User Says Thank You to Nat For This Useful Post: |

|

|

|